It’s then that I see Clint Eastwood scurry away unnoticed. I see my pig running into the ocean, his pink snout inching across the sea’s dark surface, phosphorescence glittering around his head like a crown of blue stars.

Rattawut Lapcharoensap, “Farangs” from Sightseeing (Glove Press, 2005)

The title of my project Sight Seeing is taken, rather directly, from Sightseeing by Rattawut Lapcharoensap, a short story from a book of the same title. In Sightseeing, the main character, a teenage boy, travels south by train with his mother to go to the Andaman Islands from Bangkok. The mother is losing her eyesight. From the window, he sees the railroad dividing the cobalt-blue ocean of Andaman and the more reddish, dirty waters of the Gulf of Thailand. The railroad cuts through two worlds. The mother can sometimes see the view, while some other times, she can’t. On the train, the mother tells the son about the conditions of her eyesight:

Sometimes, when she opened her eyes, the world would still be murky, blurred, like opening her eyes underwater, and it often took a while before things came back into focus again.

Rattawut Lapcharoensap, “Sightseeing” from Sightseeing (Glove Press, 2005)

Sightseeing—an excursion; a view; eyesight; perception to see . . . It refers to the excursion the main character takes with his mother. He sees the view and the light in front of his eyes, while his mother is being shut off from the world of light. The boy looks at his mother; he is helpless to cure her ability to see. Being with her, he is filled with memories from the past, while in front of him lies the future filled with possibilities. Caught between the thoughts of staying with the mother and leaving her for college, he faces the beautiful vista in front of him.

The story seemed to me like an allegory of the photographic process, the act of being exposed to light. I was about to start a new photographic project that required long exposure time; the nature of the project required a long time to record the light, to see what is in front of my eyes and the lens, so I named the series Sight Seeing (Its Japanese title is 感光 [kanko] which means exposure to light and is a homonym of 観光 [kanko], meaning sightseeing).

I read the Japanese translation of “Sightseeing” recently. In the postscript, the translator writes:

The Japanese title 観光 may seem to be the direct translation of its original English title Sightseeing. Yet there is a lot more to it. The word sightseeing combines sight (eyesight, the field of view, scenery, landscape . . . ) and seeing (to see, the visual perception . . . ), and the rich connotations match the theme of the story. Therefore I entitled it “観光,” which could also connote “seeing light.”

Midori Furuya, Translator’s Postscript from Kanko [Sightseeing] (Hayakawashobo, 2010)

“Seeing light.” As seen in the short story, light is always flickering on the other side, somewhere in between here and there. We cannot reach it no matter how hard we tried. Lapcharoensap’s short stories included in Sightseeing are filled with characters that remind me of such a light: a transcendental being; a transgender woman who jeers at men during the physical checkups for military recruitment; a pet pig named Clint Eastwood; men who are obsessed with cock-fights; a crying Filipino boy who does not speak Thai; a Cambodian refugee girl with a golden tooth; an old American man shedding tears remembering the times he shared with his dying friend, with whom he watched many spaghetti western movies. I am not sure if this was intended but they all seem strangely queer-ish to me. In the Japanese edition, the translator also mentions that the author has disappeared from the literary world. I wish I could read his new novel one day, soon.

May 2012. I returned to Okinawa to photograph a local man who volunteered to pose for my Sight Seeing project. At night, in the pouring rain—it was rainy season in Okinawa—I took a northbound bus to Ginowan city, where he lived. In his quiet, dark room, I realized that I had never photographed a man in Okinawa, nor had I ever made a portrait in Okinawa. He said he lived with his wife, who happened to be out.

Most of the models I shot for Sight Seeing were straight men, which was unexpected for me because given the tone of my work I presumed most of them would be gay. As I photographed more straight men in nude, a strange sense of rebellion towards the heterosexual society grew inside me. I thought I was making the subjects’ sexuality ambiguous by undressing them and facing them with my queer lens in such an intimate manner. It was my way of challenging masculinity and hetero-normativity. Perhaps it was too subtle an action to call a rebellion; it was more like a childish attempt at revenge.

At least, that was what I thought. The truth was that, most of the times when I was taking a photograph, I couldn’t even look at them straight; I got shy even in the dark. “Should I take off my clothes?” the model asked. They just didn’t care about being naked. That nipped off the sprout of rebelliousness that had grown within me. I was hoping that by photographing straight men, I could blur the boundary of sexuality. But it was also quite possible that I would become complicit in strengthening the framework of male chauvinism and homosocial bonds. During the shoots, I constantly had such ambivalent feelings about photographing straight men, yet the temporal relationship I formed with each one of them was more casual and intimate than I thought. I couldn’t help but feel a sense of liberation in the experience.

Now, in Okinawa, I was photographing this straight man. He was naked except for his aloha shirt. While taking pictures, he told me about the gay events in Okinawa, which he seemed to attend quite often. “It’s fun, you go to one club after another, drink, head to the beach, and keep partying and drinking until the sun rises. The party feels like it goes on forever, it’s crazy . . . ” He obviously knew more about the gay society in Okinawa than I did. Then it occurred to me. I had never been to a gay bar in Okinawa.

Ikuo Shinjo’s Okinawa wo kiku [Listening to Okinawa] reveals the political structure of postwar Okinawa, which according to the author, had been built upon the strong homosocial bond between Japan and America. Stuck in between the two, Okinawa is forced to be de-masculinized. The Okinawan men, struggling to regain their deprived masculinity, conceal the presence of people who do not follow their sexual norms, mainly the sexual minorities. The book unraveled the uneasiness I felt while living in Okinawa. The author’s words in the book’s conclusion felt especially poignant to me:

Little after I turned 30, I was struck with an intense feeling of anxiety; life became exhausting and I started to spend days in desperation. I was well aware in my twenties that my unresolved attitude towards my sexual identity often put me in despair as I kept failing to find a right place in the hetero-normative society. But in addition, I started to realize that my increasingly self-destructive behavior was interlocked with the colonial status of Okinawa and its political environment. In other words, while earnestly trying to be a part of the struggle by Okinawan people to acquire political independence, I was constantly repelled, physically and psychologically, by the masculine desire of Okinawan men that surfaced in the midst of such collective struggles [ . . . ] Infuriated to see the falsification of the memories of the battle of Okinawa, as well as the presence of the American military bases that continuously caused disturbances, I strove to be an advocate for the Okinawan voice. Yet, simultaneously, I often found myself confronted by the intense sexual discrimination that existed in the society. I had no idea what was hurting me so much, and how to put the agony I felt into words. I was just confused without a clue.

Ikuo Shinjo, Okinawa wo kiku [Listening to Okinawa] (Misuzu Shobo, 2010)

Like the author, I had difficulty coping with my own sexual identity. For me, as a teenager, living in Okinawa seemed impossible. When I was there I often felt intense discomfort for reasons I couldn’t specify. I left Okinawa at 18 and then moved to New York City at 21. There, I began to deal with my sexuality at last. But my problem has since been suspended and I have now turned 30.

One of the purposes of American Boyfriend was to find out the reason why Okinawan society seemed to brutally conceal the presence of homosexual relationships. In order to confront such repression, I once made up a fictional American man, a soldier, whom I would meet and fall in love with in Okinawa. I thought I needed to start from an intimate scale, by first de-politicizing “America” to investigate the political situation of the islands. It was also an inquiry into the possibility of a romantic relationship between an Okinawan man and an American man, which might have been formed in a clandestine manner and remained hidden. “Don’t Ask Don’t Tell,” which remained effective until recently, could be one of the reasons for the invisibility. I believe there is a hope in the possible romantic relationship between the two; for now the relationship seems carefully concealed by politics and society.

I imagine the fences falling. I imagine the vast, green forest that was once a military base. I imagine the tranquil sky. I imagine two people—two men, two women or both. I imagine an American and an Okinawan, or an Okinawan and a Japanese walking through the forest and reaching the ocean. Maybe, the difficulties of the present times are merely replaced by other difficulties. A form of violence replacing another. Yet, I want to see what they see. I want to see the world where the fences are gone, revealing the horizon in front of us, with the glittering waves washing at our feet. That would be nice.

In The Teahouse of the August Moon, an American satirical film about the U.S. army efforts to civilize Okinawans after WWII, Marlon Brando plays the role of Sakini, an Okinawan interpreter, who mischievously prompts the Americans to build a teahouse in his village, instead of the originally planned pentagon-shaped school.

In his book Okinawa wo Kiku [Listening to Okinawa], Ikuo Shinjo discusses this character as “an interpreter, a being on boundary,” a colonized man who goes in and out of the bases, agitating the intense homosocial bonds among the military personnel. Brando, 32 at the time, plays the character with his young and masculine features veiled under thick yellow makeup. He seems de-masculinized and sexually ambiguous, a harmless being. Shinjo sees in this a reflection of Okinawa itself: a feminized entity, a conduit for the political and military bond between Japan and America that is forced to accept military bases at its core.

Ten years later, Brando played middle-aged Major Penderton in Reflections on a Golden Eye. He is well over 40; his youth and delicate features are gone. The movie takes place in an army post somewhere in America. The relationship between him and his wife has long gone cold; at night, he locks himself up in the library and admires a photograph depicting a statue of a naked David. One day, Penderton takes a horse ride into the forest, and deep in the woods he finds a naked young soldier caressing a horse. Disturbed, Penderton loses control of his galloping horse and falls to the ground. Physically and emotionally hurt, Penderton lies flat on the yellow blanket of fallen leaves and abruptly bursts into tears. The naked soldier walks over him to reach the excited horse. Penderton looks up to see the soldier’s back: beautiful, David-like youth.

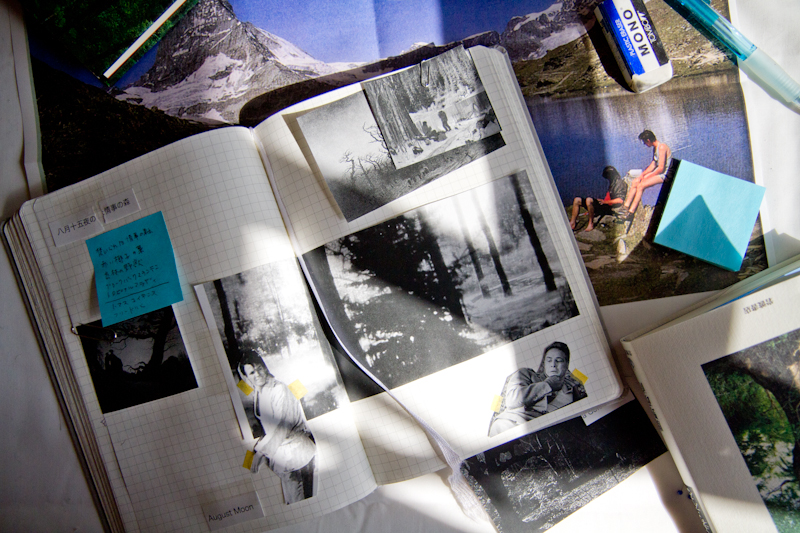

Forests have provided backdrops that stimulate clandestine meetings and transformations in movies and novels such as Brokeback Mountain, Tropical Malady, Ludwig, and The Beast in the Jungle. I cut out the photographs of Sakini and Penderton and made them face each other in a forest setting but the collage didn’t look quite right. Yet, I felt something was taking shape in the makeshift collage of Sakini and Penderton.

In the days when I was an avid reader of comic books, the line that thrilled me most, because it promised to reveal something that had been taking place at the same time as the more obvious bits of the plot, was “Meanwhile, in other part of the forest…” —usually inked in capital letters in the top left-hand corner of the box. To me (who, like any devoted reader, wished for an infinite story) this line promised something close to that infinity: the possibility of knowing what had happened on that other fork of the road, the one not yet taken, the one less in evidence, the mysterious and equally important path that led to another part of the adventurous forest.

—Alberto Manguel, Meanwhile, In Another Part of the Forest (KNOPF, 1994)

It’s a long long way but I don’t mind

there’s someone there I’ve got to find

I’m going back to Naminoue, one more time

Ronnie Fray, “Road To Naminoue ”

The road to Naminoue ran through Tsuji district. The song is about an American soldier in love with a girl working there. Tsuji’s north gate (Nishinjo) burnt down in the war.

Nishinjo was a name of the gate of Tsuji, a red light district in Naha that prospered prior to the war. Nishinjo translates to “north gate” in English. The street that ran through the gate eventually reached Shuri Castle, the royal capital of the Ryukyu Kingdom. The song “Nishinjo Bushi,” often sung as a male/female duet, tells a story of a prostitute in love with a rich man, probably a bureaucrat, working in Shuri. The two spend nights together, and they always part at the gate. “Please come with a car next time, so that we can stay longer,” begs the prostitute.

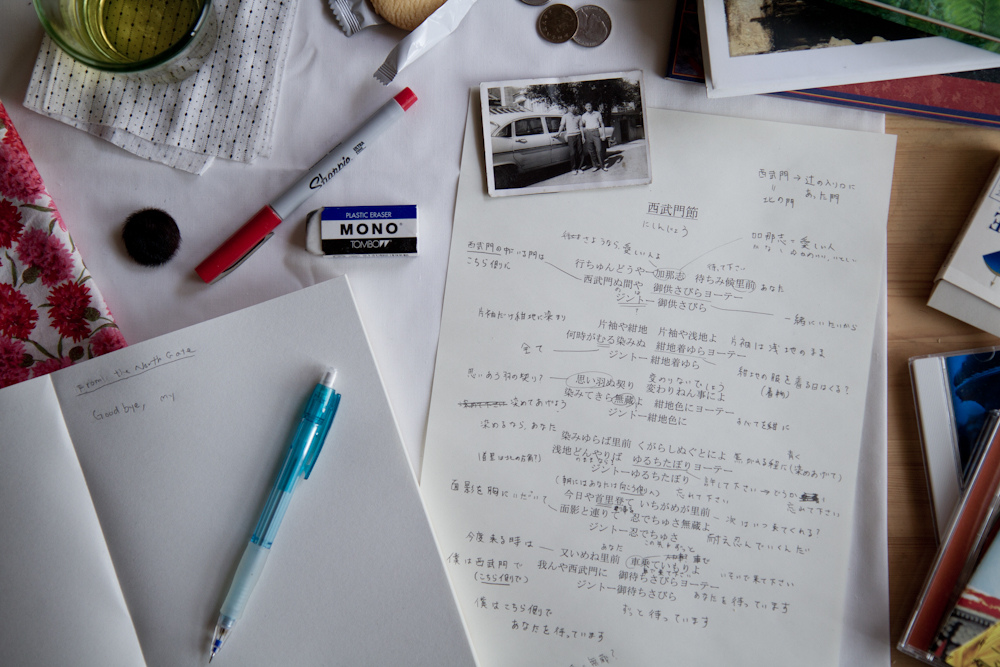

I tired to translate the song into English. To get a better understanding of the lyrics, I first needed to translate it into Japanese. Wan (first person pronoun in Okinawan) could be translated to watashi (female pronoun in Japanese) . . . or boku (male pronoun)? Then I realized that it didn’t matter because in English it would all be translated as “I.” Jo means a gate and kuruma is . . . a car. A car . . . I remembered the cars American people rode in Okinawa. They all had the character “Y” on the license plates to distinguish them from those owned by the Okinawan locals. Y-numbers (that was how we called the American owned cars) could freely go in and out of the gates of American military bases, while most of the Okinawans couldn’t. And it was those American men on Y-numbers who contributed to Tsuji thriving again after the war, albeit temporarily.

Also it was the area where the Teahouse of the August Moon was built during the American occupation-era. It became the model for the film of the same name, which told a love story between a Okinawan geisha girl and an American soldier.

March 2012, Taichung. Goro and Chris taught me how to play the sanshin. First, I used the kankara sanshin, then Goro handed me the real one. Picking its strings, I was amazed by how clear the sound was. Reading the music score and making a sound felt like learning a new language. I promised myself to buy a sanshin when I was back in Tokyo. I wanted to learn to play a song called Nishinjo Bushi, a sad song about a female prostitute waiting for a lover/customer by the gate of a red light district in which she is confined. It was my favorite Okinawan song.

In October 2011, a friend introduced me to Chris and Goro, two Taiwanese men who were visiting Tokyo. As soon as they realized that I was from Okinawa, they made me smile by greeting me in Okinawan (“Haisai!”). I later found out that Goro could play the sanshin, a traditional Okinawan three-stringed instrument and that he could also sing traditional Okinawan songs. They said they were really into Okinawan music. I, on the other hand, couldn’t play the sanshin, nor could I understand what the songs were about since I didn’t understand the Okinawan language.

In March 2012, I visited Taiwan to see Chris and Goro. I wanted to learn from them how to play the sanshin. On the day of my flight to Taiwan, I woke up too late and missed the flight; I ended up arriving in Taichung well after eleven at night, almost ten hours later than I was supposed to arrive. But Chris and Goro were there at the train station to pick me up. They then took me to the night market, where I had several strange yet delicious snacks. Next day, I met up with them and we all headed to a café near the National Museum of Fine Arts. I was walking behind them. Goro was carrying a sanshin that he had borrowed from his teacher in a black case and Chris had with him a kankara sanshin. For practice, he said. Chris spoke fluent Japanese while Goro didn’t, therefore Goro and I communicated with Chris as our interpreter. In the café’s backyard, they started to teach me how to play the instrument (that was when I realized that Chris could play it too). Later, I filmed Goro singing “Asadoya Yunta.” He played it many times so that I could later choose the footage I liked.

Back in Tokyo, I went through the videos. One take had the annoying hiss of a car on the street, another had loud voices coming from the café. But there was a take in which the noises of the afternoon café faded until a bird started to sing nearby, and a white butterfly appeared and flew around Goro. It felt like a perfect, summerly afternoon.

I always hated summer, but some afternoons I could only describe as a perfect summer afternoon, and when that happened I could forget all the distress the hot and humid season caused. In such an afternoon, I would hear the tranquil sounds of the everyday; the rustling of the sugarcane fields, the distant waves, my grandparents talking downstairs with the TV on. I could never understand my grandparents when they talked to each other in Okinawan. I wondered how Goro managed to remember the lyrics in Okinawan. In front of me, in Taiwan, he sang an Okinawan song, which seemed quite extraordinary. “Mata harinu tsundara kanushamayo,” he sang. I had no idea what that meant.

(C) 2012-2015 Futoshi Miyagi